How children spend their time in low- and middle-income countries has drawn considerable policy debate, especially with regards to 'child labour', however detailed comparative evidence on children’s time use is difficult to find. In our latest working paper we take an in-depth look at the evidence from Young Lives in an attempt to understand how much time 15-year-old girls and boys in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam are spending on work, as well as other activities such as going to school and studying. We find that where you are born matters: Ethiopian boys and girls work far more at all ages than those in other countries, and they begin working at a much younger age: 2 hours per day on average when they are age 5. Within countries, time spent on work also varies a lot between urban and rural areas, with rural children working much longer hours. Gender matters too: in all countries girls spend more time on household chores and caring for others, whereas boys work more for pay. We can also see that things are changing over time: 7 years ago, 15-year-olds were spending more time on work and less on education in India and Peru, and in rural Ethiopia.

Young Lives has followed two cohorts of children, a Younger Cohort born in 2001 and an Older Cohort born seven years earlier in 1994. In this blog we focus on those Younger Cohort individuals who were aged 15 at the latest survey round (2016). We also look at how time use has evolved as these children grow up, and how things have changed since 2009 when the Older Cohort was also age 15.

From the snapshot above, we can see that 15-year-olds across the study countries spend a similar amount of time sleeping, but that there are marked differences in the proportion of time spent on work and education. In Ethiopia, both boys and girls are working for an average of 4.5 hours, whereas in Peru and India it is just over 2 hours. Meanwhile, 15-year-olds in India are spending almost 10 hours per day on school and studying. These averages include boys and girls in urban and rural settings, and those in and out of school.

Young Lives and time use

Young Lives started collecting time use information from the 12,000 Young Lives children plus all school-aged children living in their households back in 2006. At that time, the Younger Cohort children were just 5 years old. We asked them to tell us how they spend their time on a typical day. At the age of 5, the question was asked to their main caregiver. We collected this information systematically in the following survey rounds when children were age eight (in 2009) and age 12 (in 2013) – the age from which children were asked directly about their own time use. The latest survey round in 2016 asked this same question, marking a decade since we first started exploring how the Young Lives children spend their time.

Comparing the caregiver and child reports show that who responds to these questions does make a difference. We find that children themselves report significantly more time spent on work than their caregivers, although the average difference is fairly small (about ten minutes per day).

The question about time use refers specifically to a typical day, during weekdays, in the last week. Every survey round was programmed to take place during each country’s academic year. Therefore, the question on time use implicitly refers to a typical day when school was in session (note that underreporting of time spent on work is likely given that it is probably higher at weekends and during school holidays). Children (and their caregivers) were asked how they allocate their time across eight different activities including: at school and studying outside of school (which we classify here as time spent on education); a range of tasks that children undertake within and outside their households such as caring for other people; household chores; working without pay at home (on the family farm or business); and working for pay (outside the household which we classify here as time spent on work); and finally relaxing/leisure, and sleeping.

The way the data were collected varied slightly across countries. In Ethiopia, India and Vietnam children were offered 24 pebbles/seeds (representing hours in the day) to be placed into the eight categories while Peru followed a recall method. The latter allows capturing simultaneous activities (e.g. doing household chores while also caring for younger siblings), whereas the former captures primary activities (e.g. if respondent was cooking and looking after young children, the respondent will select the one that was most important at the time).

The above graphic shows a snapshot of all the children in the Young Lives households aged 5-17, the amount of time they spend on education (in red) and the amount of time in work (in blue). Noting that work includes all kinds of work (household chores, caring for others, work in the household farm or business, and paid work outside the household) we can see that Ethiopian boys and girls work much more than children in the other study countries at all ages. Even at the age of 5, the average hours worked per day is 2, which is equivalent to the amount of work of 15-year-olds in the other countries. Time spent in work increases steadily and plateaus between the ages of 10 and 14 years, then increases again as children start dropping out of school (mirrored by the corresponding fall in education hours). In all countries, for younger children, growing up is associated with an increase in both education and work. However, in early adolescence, time spent on education and work appear to be substitutes for each other.

We now pay closer attention to these variations across country, gender and location in education and work.

On education

It is clear that one of the main factors influencing how 15-year-olds spend their time is whether or not they are still in school. In 2016 the majority of children in all four countries were still attending school at age 15, though more of them were in school in 2013 when they were 12 years old, indicating that a growing number have started to drop out of school.

The rates at which children leave school vary across countries, location and gender. Urban 15-year-olds are much more likely to be in school in all four study countries. Surprisingly, perhaps, girls are more likely to remain in school at age 15 in all countries except India: 97% of young women in Peru and 93% in Ethiopia are attending school. This compares with fewer than three-quarters of Vietnamese boys in rural areas. Almost half of those who left school in Vietnam said that it was because they were suspended for being absent for too long. The enrolment rate also fell in India from 96% at the age of 12 to about 88% at age 15. In India, girls were more likely to leave school than boys with one of the main reasons being marriage.

We note here that, unfortunately, attendance at school is not perfectly correlated with higher learning outcomes, as much depends on school quality. Researchers from Young Lives discuss such issues in more depth here and the World Bank summarises key policy recommendations from its latest World Development Report around education here.

On work

Young Lives data show that the amount of time spent working varies greatly by gender and location (both in terms of country and urban or rural base). As we noted previously, at all ages – even at the age of five – children from the Ethiopian study sites spent more time working than those in India, Peru and Vietnam. At the age of 15, both boys and girls in Ethiopia spent around 4.5 hours per day helping around the house, and in paid and unpaid work, double the amount of time spent by 15-year-olds in India. A related blog by Alula Pankhurst discusses this in more detail.

Most of the work undertaken by those aged 15 and under in all countries takes place within the household environment. This takes several forms but time spent doing household chores – cleaning, cooking, fetching water, collecting firewood – is the most prevalent in all four countries. The work that boys do is mainly oriented around helping with farm-related activities, while girls undertake more housework. Policymakers are acknowledging more that the work done by children is often unpaid, and often by girls (more information in the summative report from Young Lives, Responding to children’s work: Evidence from the Young Lives study in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam). However, in Ethiopia, Peru and Vietnam, boys and girls generally spend similar amounts of time on work (broadly defined) as they age. India is the exception to this, with girls at age 15 working significantly more than boys, in particular girls living in in rural areas where they spend on average 3 hours in work per day.

The incidence of paid work is fairly low, and this may be partly due to the question being asked about a typical day during weekdays. Grace Chang explores trends in time spent on paid work using another question that recalls work over the past year here.

Combining work and school is the norm for most children

Child work has been highly debated and the related Sustainable Development Goal target is to end the worst forms of child labour and all child labour by 2025, just seven years from now. One of the assumptions is that time spent working is detrimental to children’s education. However, Young Lives data and analysis, both quantitative and qualitative has shown that this picture is far more complex. Children usually combine work with school with their studies, and sometimes work is the means by which they pay for such education, and a source of pride and skills building (Pankhurst, Crivello & Tiumelissan, 2016; Morrow, 2015). On the other hand, Young Lives research has shown that if children work too many hours, this may have detrimental effects on their schooling (Tafere & Pankhurst, 2015; Woldehanna & Gebremedhin, 2015).

The overall story we see is that 15-year-old boys are slightly more likely to leave school than girls in order to pursue full time work – however, when combining school and work, girls are spending slightly more time on work than boys. On average, those who are not in school work 5+ hours more than those who are in school, though we do not give this a causal interpretation.

Life is changing for 15-year-olds, especially for girls in rural areas

Given the 2025 deadline for eliminating the worst forms of child labour, Young Lives can offer a unique insight into what may happen over the next seven years. The Young Lives study benefits from following two cohorts born seven years apart, so allowing us to compare how life has changed for our Younger Cohort 15-year-olds since the Older Cohort turned 15 in 2009, seven years ago.

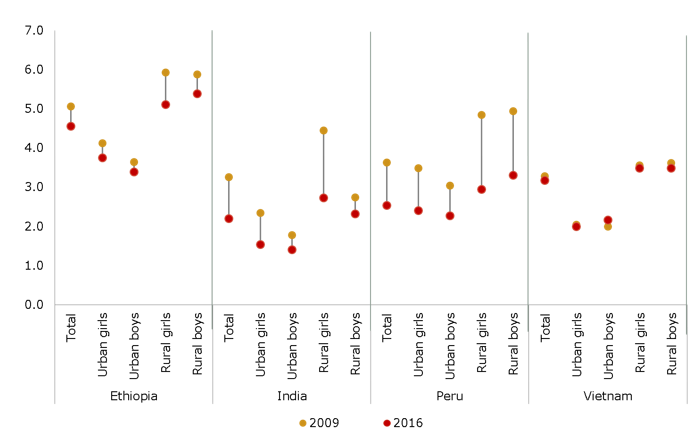

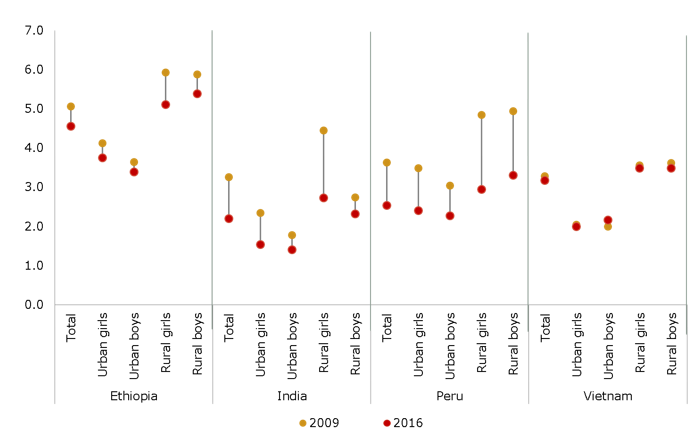

In India and Peru, 15-year-olds in 2016 worked on average one hour less per day than those in 2009. In Ethiopia, time spent on worok has fallen by just 30 minutes over seven years, and in Vietnam there is no change, meaning that India and Peru have closed the gap in terms of hours spent working and are now comparable to Vietnam. In both India and Peru the changes have been driven by rural children, and by girls – meaning that whilst rural children work more than urban children, and girls work more than boys, the gap was narrower in 2016 than it was in 2009.

By 2016, the Older Cohort individuals were around 22 years of age, and many had left or finished schooling and moved into full time work. For children from the poorest households, this was often in the informal sector, often with little job security. At this age, the balance of work/education shifted towards work: about half of all 22-year-olds in Ethiopia, India and Peru, and three quarters of those in Vietnam declared being exclusively working (not studying). The proportion of young people who reported being exclusively studying (not working) varied quite a lot across countries being the highest in Ethiopia (20%) and the lowest in Vietnam (6%). At this age, one fifth of young adults in Peru combined work and education – the highest among the four countries – and a quarter of those in India reported being involved in neither activity; the proportions are significantly lower in the rest of the countries.

Of course this blog only glances at of how the Young Lives children spend their time. We have only been able to outline the trends at a very broad level by country, location and gender. Our working paper further explores the factors correlated with changes in time spent working over the life course.

__________________________________________

For related findings and discussions, please follow Young Lives on Twitter @yloxford and see key materials following:

- Jo Boyden reflects on policy responses to child labour here

- Keetie Roelen discusses social protection and its links to child labour here

- Explore the data yourself through Young Lives' data visualizations

How children spend their time in low- and middle-income countries has drawn considerable policy debate, especially with regards to 'child labour', however detailed comparative evidence on children’s time use is difficult to find. In our latest working paper we take an in-depth look at the evidence from Young Lives in an attempt to understand how much time 15-year-old girls and boys in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam are spending on work, as well as other activities such as going to school and studying. We find that where you are born matters: Ethiopian boys and girls work far more at all ages than those in other countries, and they begin working at a much younger age: 2 hours per day on average when they are age 5. Within countries, time spent on work also varies a lot between urban and rural areas, with rural children working much longer hours. Gender matters too: in all countries girls spend more time on household chores and caring for others, whereas boys work more for pay. We can also see that things are changing over time: 7 years ago, 15-year-olds were spending more time on work and less on education in India and Peru, and in rural Ethiopia.

Young Lives has followed two cohorts of children, a Younger Cohort born in 2001 and an Older Cohort born seven years earlier in 1994. In this blog we focus on those Younger Cohort individuals who were aged 15 at the latest survey round (2016). We also look at how time use has evolved as these children grow up, and how things have changed since 2009 when the Older Cohort was also age 15.

From the snapshot above, we can see that 15-year-olds across the study countries spend a similar amount of time sleeping, but that there are marked differences in the proportion of time spent on work and education. In Ethiopia, both boys and girls are working for an average of 4.5 hours, whereas in Peru and India it is just over 2 hours. Meanwhile, 15-year-olds in India are spending almost 10 hours per day on school and studying. These averages include boys and girls in urban and rural settings, and those in and out of school.

Young Lives and time use

Young Lives started collecting time use information from the 12,000 Young Lives children plus all school-aged children living in their households back in 2006. At that time, the Younger Cohort children were just 5 years old. We asked them to tell us how they spend their time on a typical day. At the age of 5, the question was asked to their main caregiver. We collected this information systematically in the following survey rounds when children were age eight (in 2009) and age 12 (in 2013) – the age from which children were asked directly about their own time use. The latest survey round in 2016 asked this same question, marking a decade since we first started exploring how the Young Lives children spend their time.

Comparing the caregiver and child reports show that who responds to these questions does make a difference. We find that children themselves report significantly more time spent on work than their caregivers, although the average difference is fairly small (about ten minutes per day).

The question about time use refers specifically to a typical day, during weekdays, in the last week. Every survey round was programmed to take place during each country’s academic year. Therefore, the question on time use implicitly refers to a typical day when school was in session (note that underreporting of time spent on work is likely given that it is probably higher at weekends and during school holidays). Children (and their caregivers) were asked how they allocate their time across eight different activities including: at school and studying outside of school (which we classify here as time spent on education); a range of tasks that children undertake within and outside their households such as caring for other people; household chores; working without pay at home (on the family farm or business); and working for pay (outside the household which we classify here as time spent on work); and finally relaxing/leisure, and sleeping.

The way the data were collected varied slightly across countries. In Ethiopia, India and Vietnam children were offered 24 pebbles/seeds (representing hours in the day) to be placed into the eight categories while Peru followed a recall method. The latter allows capturing simultaneous activities (e.g. doing household chores while also caring for younger siblings), whereas the former captures primary activities (e.g. if respondent was cooking and looking after young children, the respondent will select the one that was most important at the time).

The above graphic shows a snapshot of all the children in the Young Lives households aged 5-17, the amount of time they spend on education (in red) and the amount of time in work (in blue). Noting that work includes all kinds of work (household chores, caring for others, work in the household farm or business, and paid work outside the household) we can see that Ethiopian boys and girls work much more than children in the other study countries at all ages. Even at the age of 5, the average hours worked per day is 2, which is equivalent to the amount of work of 15-year-olds in the other countries. Time spent in work increases steadily and plateaus between the ages of 10 and 14 years, then increases again as children start dropping out of school (mirrored by the corresponding fall in education hours). In all countries, for younger children, growing up is associated with an increase in both education and work. However, in early adolescence, time spent on education and work appear to be substitutes for each other.

We now pay closer attention to these variations across country, gender and location in education and work.

On education

It is clear that one of the main factors influencing how 15-year-olds spend their time is whether or not they are still in school. In 2016 the majority of children in all four countries were still attending school at age 15, though more of them were in school in 2013 when they were 12 years old, indicating that a growing number have started to drop out of school.

The rates at which children leave school vary across countries, location and gender. Urban 15-year-olds are much more likely to be in school in all four study countries. Surprisingly, perhaps, girls are more likely to remain in school at age 15 in all countries except India: 97% of young women in Peru and 93% in Ethiopia are attending school. This compares with fewer than three-quarters of Vietnamese boys in rural areas. Almost half of those who left school in Vietnam said that it was because they were suspended for being absent for too long. The enrolment rate also fell in India from 96% at the age of 12 to about 88% at age 15. In India, girls were more likely to leave school than boys with one of the main reasons being marriage.

We note here that, unfortunately, attendance at school is not perfectly correlated with higher learning outcomes, as much depends on school quality. Researchers from Young Lives discuss such issues in more depth here and the World Bank summarises key policy recommendations from its latest World Development Report around education here.

On work

Young Lives data show that the amount of time spent working varies greatly by gender and location (both in terms of country and urban or rural base). As we noted previously, at all ages – even at the age of five – children from the Ethiopian study sites spent more time working than those in India, Peru and Vietnam. At the age of 15, both boys and girls in Ethiopia spent around 4.5 hours per day helping around the house, and in paid and unpaid work, double the amount of time spent by 15-year-olds in India. A related blog by Alula Pankhurst discusses this in more detail.

Most of the work undertaken by those aged 15 and under in all countries takes place within the household environment. This takes several forms but time spent doing household chores – cleaning, cooking, fetching water, collecting firewood – is the most prevalent in all four countries. The work that boys do is mainly oriented around helping with farm-related activities, while girls undertake more housework. Policymakers are acknowledging more that the work done by children is often unpaid, and often by girls (more information in the summative report from Young Lives, Responding to children’s work: Evidence from the Young Lives study in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam). However, in Ethiopia, Peru and Vietnam, boys and girls generally spend similar amounts of time on work (broadly defined) as they age. India is the exception to this, with girls at age 15 working significantly more than boys, in particular girls living in in rural areas where they spend on average 3 hours in work per day.

The incidence of paid work is fairly low, and this may be partly due to the question being asked about a typical day during weekdays. Grace Chang explores trends in time spent on paid work using another question that recalls work over the past year here.

Combining work and school is the norm for most children

Child work has been highly debated and the related Sustainable Development Goal target is to end the worst forms of child labour and all child labour by 2025, just seven years from now. One of the assumptions is that time spent working is detrimental to children’s education. However, Young Lives data and analysis, both quantitative and qualitative has shown that this picture is far more complex. Children usually combine work with school with their studies, and sometimes work is the means by which they pay for such education, and a source of pride and skills building (Pankhurst, Crivello & Tiumelissan, 2016; Morrow, 2015). On the other hand, Young Lives research has shown that if children work too many hours, this may have detrimental effects on their schooling (Tafere & Pankhurst, 2015; Woldehanna & Gebremedhin, 2015).

The overall story we see is that 15-year-old boys are slightly more likely to leave school than girls in order to pursue full time work – however, when combining school and work, girls are spending slightly more time on work than boys. On average, those who are not in school work 5+ hours more than those who are in school, though we do not give this a causal interpretation.

Life is changing for 15-year-olds, especially for girls in rural areas

Given the 2025 deadline for eliminating the worst forms of child labour, Young Lives can offer a unique insight into what may happen over the next seven years. The Young Lives study benefits from following two cohorts born seven years apart, so allowing us to compare how life has changed for our Younger Cohort 15-year-olds since the Older Cohort turned 15 in 2009, seven years ago.

In India and Peru, 15-year-olds in 2016 worked on average one hour less per day than those in 2009. In Ethiopia, time spent on worok has fallen by just 30 minutes over seven years, and in Vietnam there is no change, meaning that India and Peru have closed the gap in terms of hours spent working and are now comparable to Vietnam. In both India and Peru the changes have been driven by rural children, and by girls – meaning that whilst rural children work more than urban children, and girls work more than boys, the gap was narrower in 2016 than it was in 2009.

By 2016, the Older Cohort individuals were around 22 years of age, and many had left or finished schooling and moved into full time work. For children from the poorest households, this was often in the informal sector, often with little job security. At this age, the balance of work/education shifted towards work: about half of all 22-year-olds in Ethiopia, India and Peru, and three quarters of those in Vietnam declared being exclusively working (not studying). The proportion of young people who reported being exclusively studying (not working) varied quite a lot across countries being the highest in Ethiopia (20%) and the lowest in Vietnam (6%). At this age, one fifth of young adults in Peru combined work and education – the highest among the four countries – and a quarter of those in India reported being involved in neither activity; the proportions are significantly lower in the rest of the countries.

Of course this blog only glances at of how the Young Lives children spend their time. We have only been able to outline the trends at a very broad level by country, location and gender. Our working paper further explores the factors correlated with changes in time spent working over the life course.

__________________________________________

For related findings and discussions, please follow Young Lives on Twitter @yloxford and see key materials following:

- Jo Boyden reflects on policy responses to child labour here

- Keetie Roelen discusses social protection and its links to child labour here

- Explore the data yourself through Young Lives' data visualizations