Douglas Scott (Research Officer, Young Lives) breaks down the research behind a new paper (published in Social Science & Medicine - Population Health Journal and authored by Marta Favara, Catherine Porter, Alan Sánchez and Douglas Scott) quantifying the increase in physical domestic violence (family or intimate partner violence) experienced by young people aged 18–26 during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns in Peru using data from the Young Lives at Work Covid phone surveys.

Shining a light on the Shadow Pandemic in Peru

While the global issue of domestic abuse is certainly not a new one, there now exists mounting evidence of a link between increasing violence against women and girls, and stay-at-home requirements or lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic. This alarming rise in violence, referred to as the “Shadow Pandemic” by the United Nations, has led many to suggest that the same policies enacted by governments to protect citizens from the Covid-19 virus may, in fact, be placing some individuals directly in harm’s way.

In this recent paper by the Young Lives team, we measure the increase in physical domestic violence experienced by young people (aged 18-26), during the strict and lengthy Covid-19 lockdowns in Peru. We rely on an approach known as List Randomization, which gives a level of anonymity to responses to sensitive questions, potentially allowing individuals to provide more truthful answers than they might if asked directly about a sensitive topic.

Our results are based on information collected as part of the Young Lives longitudinal study, which tracks 12,000 children (now adolescents and young adults) in Ethiopia, India (Telangana and Andhra Pradesh), Peru, and Vietnam. Before the pandemic, these respondents and their households had been visited in-person during 5 survey rounds from 2002-2016. However, as a result of the outbreak, we replaced the planned 6th round with a three-part phone survey, aimed at collecting information on experiences related to pandemic. The List Randomization Experiment was included in the 2nd call of the phone survey, which took place between 18th August and 15th October of 2020.

Covid, lockdowns and a history of violence

The choice of Peru as the focus of this paper owes much to the country’s experiences with Covid-19, and the exceptionally strict response of the national government. Peru occupied the highest position in the global rankings of Covid-19 cases and deaths per capita during most of 2020, despite extremely lengthy and restrictive stay-at-home requirements.

The graph below shows the timeline of confirmed Covid cases in Peru during 2020. The grey line marks the end of a nationally-imposed period of lockdown, between 16th March and 30th June, while the yellow line shows the end of a subsequent period of more localized lockdowns between July, August and September. The dates bounded by the two red lines represent the earliest and latest dates where the information on domestic violence was collected during the phone survey.

Source: Government of Peru

Fig 1. The number of positive Covid-19 cases in Peru during 2020 (in thousands).

Aside from Peru’s experiences with the Covid-19 virus, the country also has historically high levels of domestic violence. An earlier wave of the Young Lives study (in 2016) found that 20-23% of girls and 9-10% of boys had experienced physical violence, perpetrated by a spouse/partner or another family member, at some point in their lives. In addition to this, evidence from phone calls to the helpline for domestic abuse (Línea 100) suggests that violence against women increased by around 48% between April and July 2020.

Measuring violence

To measure the increase in domestic violence during lockdowns we use an indirect approach, the List Randomization Experiment. If implemented well, this method should minimize the likelihood of under-reporting due to the sensitive subject matter, and also limit the ethical concerns around directly asking a question on domestic violence to an individual who potentially may have been a victim. Given the age of our respondents, we were keen to reflect a situation where any family member could be a perpetrator of violence (not just an intimate partner) and, rather than focus only on woman and girls, we also considered young men as potential victims.

The essence of the List Experiment is to embed a sensitive statement amongst a list of other non-sensitive statements, and ask respondents only about how many statements they agree with. Its origins lie in sociological studies which tried to elicit controversial opinions (around topics such as racism or homophobia, for example) that survey participants may have been reluctant to admit to if asked directly. The principle is similar for sensitive issues such as domestic violence.

During our List Experiment, we randomly assigned our respondents to an initial treatment and control group. Those in the control group were read a list of four (non-sensitive) statements, which did not relate to violence, but did relate to their experiences during the lockdowns. Those in the treatment group were read the same four statements, plus one additional (sensitive) statement related to experiences of physical violence. In both cases, after hearing all statements (four for the control and five for the treatment group), individuals were asked how many statements apply to them. Crucially, they were never asked to confirm or deny any one specific statement, allowing them a greater level of protection to report their answers truthfully.

In the paper, we use a version of the experiment referred to as double list randomization. This involves a second list, with a new set of non-sensitive statements, but the same statement relating to violence. In this second experiment, the treatment and control groups are reversed, such that an individual who was in the control group is now in the treatment group, and vice-versa. The questions used in both experiments are listed in the table below:

|

List 1 |

|

|

List 2 |

|

One way to measure the % of the sample who would say “Yes” to the statement on violence would be to subtract the average number of statements agreed with by the control group (out of a possible four) from the average number of statements agreed with by the treatment group (out of a possible five). For example, if (on average) the control group agreed with 2.8 statements and the treatment group agreed with 3.2 statements, this would imply a prevalence of 0.4 (40%). This could be done for either list separately, or a joint measure created from both. While the general principle remains the same, to predict both the proportion who experienced more violence, but also to determine which individual characteristics are associated with these experiences, in the paper we employ a two-stage regression model, as opposed to the difference in means approach described above.

Who are the most vulnerable during lockdowns?

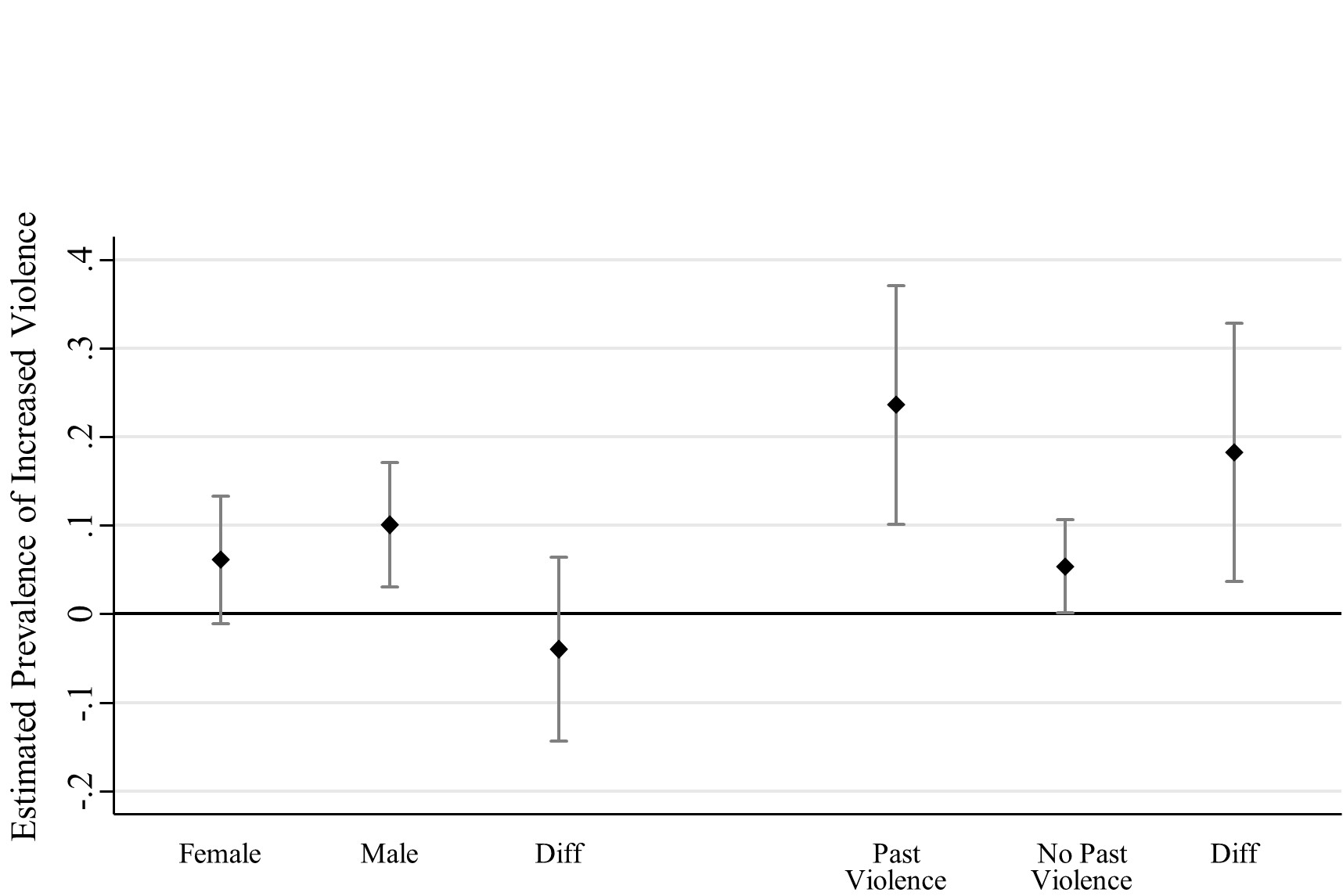

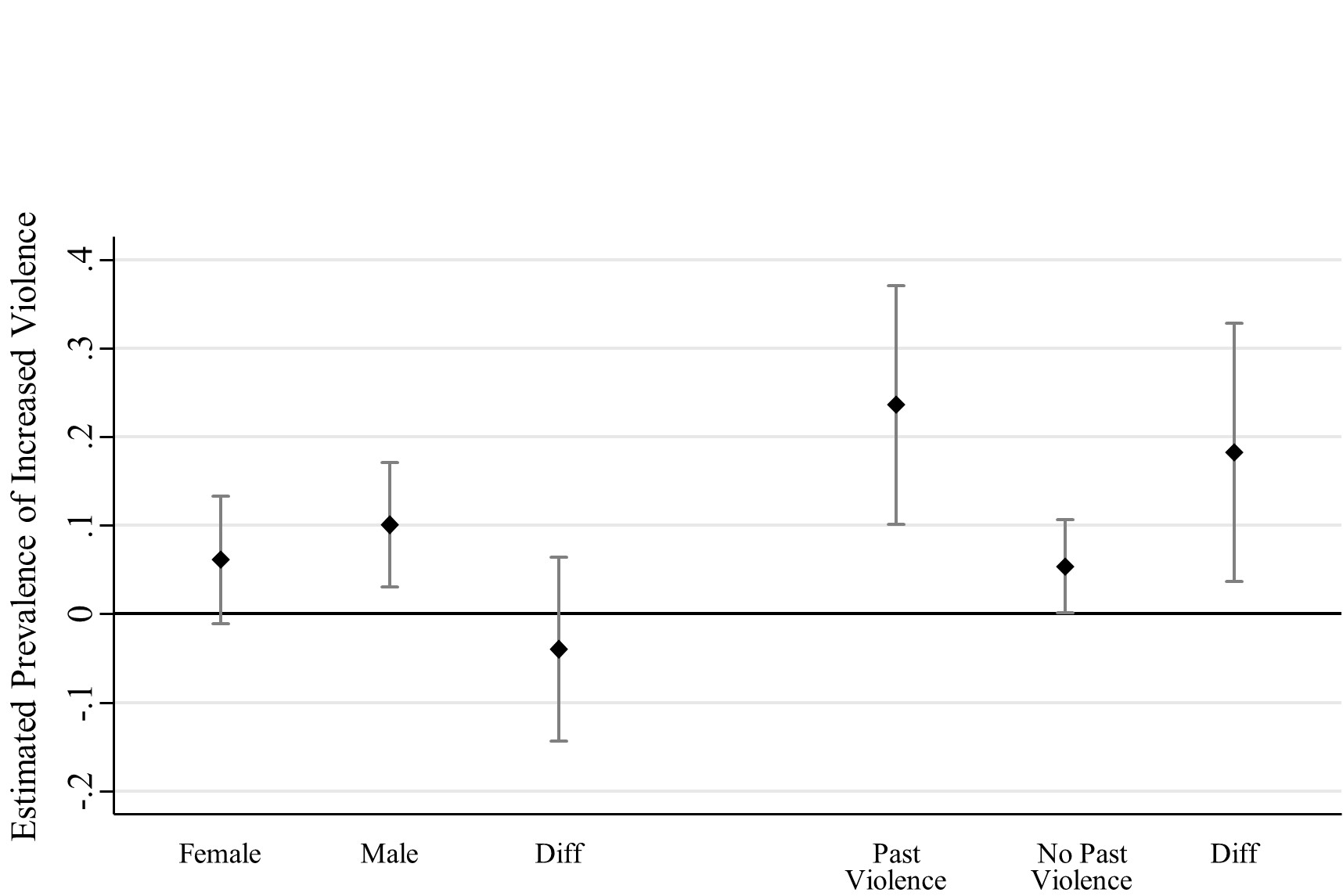

From the full sample of 1,841, we find that 8.3% of young people experienced an increase in physical domestic violence during the lockdowns. While this result was clearly important, we also wanted to dig deeper into which groups were more likely to have been affected.

Perhaps surprisingly, we found that the likelihood of experiencing an increase in violence was no greater for women than men. While the underlying (baseline) level of violence for women, measured in 2016, was double that of men (20-23% compared to 9-10%), an increase in violence during the lockdowns was no more likely for either gender.

The characteristic which proved to be the strongest predictor of experiencing more violence during the lockdown was the baseline measure of physical violence from 2016. The probability of experiencing more abuse was 23.6% for those who reported past violence in the previous survey, relative to 5.4% for those who did not. The group-specific prevalence for males and female, and those with and without a reported history of domestic violence are shown in Figure 2 below.

Fig 2. Group-specific measures of those affected by increased violence during lockdown.

Note: Predictions for each group are calculated at the sample mean of all other covariates.

Bars indicate a 95% confidence interval around predictions.

Breaking the link between lockdowns and violence

As Peru battles the latest wave of Covid-19 infections with renewed restrictions on movement, those vulnerable to domestic abuse may again find themselves trapped by the very measures aimed to keep them safe. The research conducted by Young Lives sheds light on the likely characteristics of these individuals, and a potential role for policymakers in protecting those most likely to be the victims of violence during these challenging times. In particular, a different story emerges from that which many would have expected. While there clearly exists some risk of experiencing an escalation in domestic violence during lockdowns for all groups, in most cases, simply imposing these restrictions does not inevitably lead to a pattern of domestic abuse. The increased risk to those who have already faced domestic violence in the past stands out as far more concerning, however. For this group, representing around 1-in-7 respondents in our study, the threat of infection may not be the only new danger sparked by the pandemic.

Read the full article at SSM – Population Health.

Follow us on Twitter @yloxford for news on Young LIves at Work.

Douglas Scott (Research Officer, Young Lives) breaks down the research behind a new paper (published in Social Science & Medicine - Population Health Journal and authored by Marta Favara, Catherine Porter, Alan Sánchez and Douglas Scott) quantifying the increase in physical domestic violence (family or intimate partner violence) experienced by young people aged 18–26 during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns in Peru using data from the Young Lives at Work Covid phone surveys.

Shining a light on the Shadow Pandemic in Peru

While the global issue of domestic abuse is certainly not a new one, there now exists mounting evidence of a link between increasing violence against women and girls, and stay-at-home requirements or lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic. This alarming rise in violence, referred to as the “Shadow Pandemic” by the United Nations, has led many to suggest that the same policies enacted by governments to protect citizens from the Covid-19 virus may, in fact, be placing some individuals directly in harm’s way.

In this recent paper by the Young Lives team, we measure the increase in physical domestic violence experienced by young people (aged 18-26), during the strict and lengthy Covid-19 lockdowns in Peru. We rely on an approach known as List Randomization, which gives a level of anonymity to responses to sensitive questions, potentially allowing individuals to provide more truthful answers than they might if asked directly about a sensitive topic.

Our results are based on information collected as part of the Young Lives longitudinal study, which tracks 12,000 children (now adolescents and young adults) in Ethiopia, India (Telangana and Andhra Pradesh), Peru, and Vietnam. Before the pandemic, these respondents and their households had been visited in-person during 5 survey rounds from 2002-2016. However, as a result of the outbreak, we replaced the planned 6th round with a three-part phone survey, aimed at collecting information on experiences related to pandemic. The List Randomization Experiment was included in the 2nd call of the phone survey, which took place between 18th August and 15th October of 2020.

Covid, lockdowns and a history of violence

The choice of Peru as the focus of this paper owes much to the country’s experiences with Covid-19, and the exceptionally strict response of the national government. Peru occupied the highest position in the global rankings of Covid-19 cases and deaths per capita during most of 2020, despite extremely lengthy and restrictive stay-at-home requirements.

The graph below shows the timeline of confirmed Covid cases in Peru during 2020. The grey line marks the end of a nationally-imposed period of lockdown, between 16th March and 30th June, while the yellow line shows the end of a subsequent period of more localized lockdowns between July, August and September. The dates bounded by the two red lines represent the earliest and latest dates where the information on domestic violence was collected during the phone survey.

Source: Government of Peru

Fig 1. The number of positive Covid-19 cases in Peru during 2020 (in thousands).

Aside from Peru’s experiences with the Covid-19 virus, the country also has historically high levels of domestic violence. An earlier wave of the Young Lives study (in 2016) found that 20-23% of girls and 9-10% of boys had experienced physical violence, perpetrated by a spouse/partner or another family member, at some point in their lives. In addition to this, evidence from phone calls to the helpline for domestic abuse (Línea 100) suggests that violence against women increased by around 48% between April and July 2020.

Measuring violence

To measure the increase in domestic violence during lockdowns we use an indirect approach, the List Randomization Experiment. If implemented well, this method should minimize the likelihood of under-reporting due to the sensitive subject matter, and also limit the ethical concerns around directly asking a question on domestic violence to an individual who potentially may have been a victim. Given the age of our respondents, we were keen to reflect a situation where any family member could be a perpetrator of violence (not just an intimate partner) and, rather than focus only on woman and girls, we also considered young men as potential victims.

The essence of the List Experiment is to embed a sensitive statement amongst a list of other non-sensitive statements, and ask respondents only about how many statements they agree with. Its origins lie in sociological studies which tried to elicit controversial opinions (around topics such as racism or homophobia, for example) that survey participants may have been reluctant to admit to if asked directly. The principle is similar for sensitive issues such as domestic violence.

During our List Experiment, we randomly assigned our respondents to an initial treatment and control group. Those in the control group were read a list of four (non-sensitive) statements, which did not relate to violence, but did relate to their experiences during the lockdowns. Those in the treatment group were read the same four statements, plus one additional (sensitive) statement related to experiences of physical violence. In both cases, after hearing all statements (four for the control and five for the treatment group), individuals were asked how many statements apply to them. Crucially, they were never asked to confirm or deny any one specific statement, allowing them a greater level of protection to report their answers truthfully.

In the paper, we use a version of the experiment referred to as double list randomization. This involves a second list, with a new set of non-sensitive statements, but the same statement relating to violence. In this second experiment, the treatment and control groups are reversed, such that an individual who was in the control group is now in the treatment group, and vice-versa. The questions used in both experiments are listed in the table below:

|

List 1 |

|

|

List 2 |

|

One way to measure the % of the sample who would say “Yes” to the statement on violence would be to subtract the average number of statements agreed with by the control group (out of a possible four) from the average number of statements agreed with by the treatment group (out of a possible five). For example, if (on average) the control group agreed with 2.8 statements and the treatment group agreed with 3.2 statements, this would imply a prevalence of 0.4 (40%). This could be done for either list separately, or a joint measure created from both. While the general principle remains the same, to predict both the proportion who experienced more violence, but also to determine which individual characteristics are associated with these experiences, in the paper we employ a two-stage regression model, as opposed to the difference in means approach described above.

Who are the most vulnerable during lockdowns?

From the full sample of 1,841, we find that 8.3% of young people experienced an increase in physical domestic violence during the lockdowns. While this result was clearly important, we also wanted to dig deeper into which groups were more likely to have been affected.

Perhaps surprisingly, we found that the likelihood of experiencing an increase in violence was no greater for women than men. While the underlying (baseline) level of violence for women, measured in 2016, was double that of men (20-23% compared to 9-10%), an increase in violence during the lockdowns was no more likely for either gender.

The characteristic which proved to be the strongest predictor of experiencing more violence during the lockdown was the baseline measure of physical violence from 2016. The probability of experiencing more abuse was 23.6% for those who reported past violence in the previous survey, relative to 5.4% for those who did not. The group-specific prevalence for males and female, and those with and without a reported history of domestic violence are shown in Figure 2 below.

Fig 2. Group-specific measures of those affected by increased violence during lockdown.

Note: Predictions for each group are calculated at the sample mean of all other covariates.

Bars indicate a 95% confidence interval around predictions.

Breaking the link between lockdowns and violence

As Peru battles the latest wave of Covid-19 infections with renewed restrictions on movement, those vulnerable to domestic abuse may again find themselves trapped by the very measures aimed to keep them safe. The research conducted by Young Lives sheds light on the likely characteristics of these individuals, and a potential role for policymakers in protecting those most likely to be the victims of violence during these challenging times. In particular, a different story emerges from that which many would have expected. While there clearly exists some risk of experiencing an escalation in domestic violence during lockdowns for all groups, in most cases, simply imposing these restrictions does not inevitably lead to a pattern of domestic abuse. The increased risk to those who have already faced domestic violence in the past stands out as far more concerning, however. For this group, representing around 1-in-7 respondents in our study, the threat of infection may not be the only new danger sparked by the pandemic.

Read the full article at SSM – Population Health.

Follow us on Twitter @yloxford for news on Young LIves at Work.